A TALE OF 2 ‘BOOKS’: Educators, students weigh in on teaching tools

Published 2:27 pm Friday, January 25, 2019

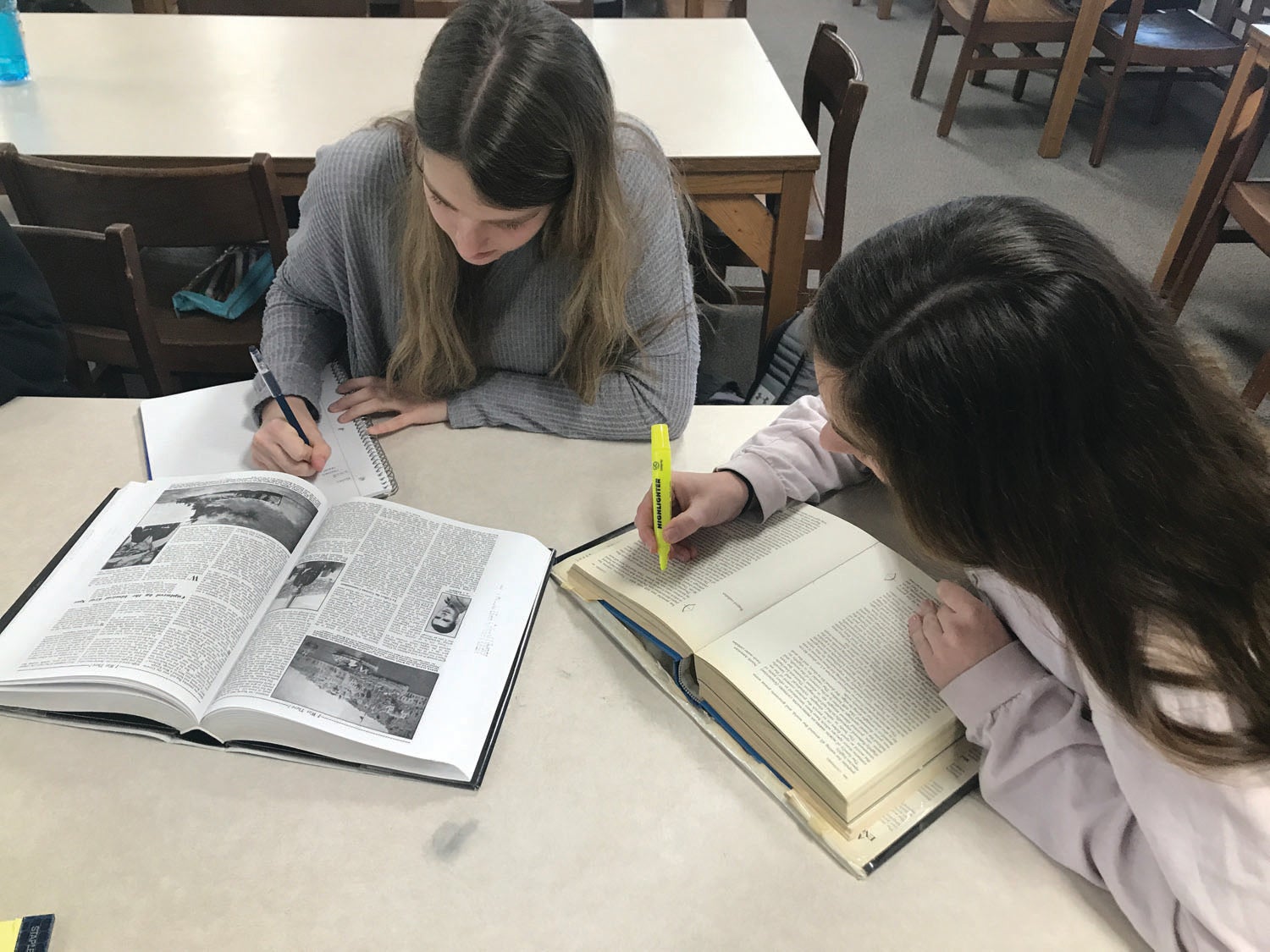

- West Stanly High senior Gretchen Castelloe, left, and junior Katherine Pollard read and highlight information from a textbook.

West Stanly High senior Gretchen Castelloe prefers textbooks over Chromebooks because “you know the information there is accurate and sound and … all the information is coming from the same place.”

But Castelloe admitted Google Chromebooks “are definitely convenient being that they’re not 400 pounds and they offer a much more affordable option.”

One of the biggest transitions in Stanly County Schools over the last decade — and most likely in many school systems across the country — has been the transition from textbooks to Chromebooks in the classroom. And many people have opinions.

The transition started around the time of the recession of 2008. State budgets had to be curtailed and one of those was for textbooks, said Shawn Britt, chief technology officer for Stanly County Schools.

“Everything comes down to economics,” he said.

The data backs it up.

During the 2007-2008 school year, according to data from the Department of Public Instruction, the total textbook sales in North Carolina was more than $79 million. The next school year (2008-2009), the total textbook sales plummeted to just over $51 million — and it’s been decreasing, for the most part, ever since.

For the 2014-2015 school year, total textbooks sales were only $3 million.

“I think the biggest thing is people think that it’s a choice (of choosing between Chromebooks or textbooks), but it’s not a choice,” said Danny Poplin, executive director of curriculum and instruction for SCS. “It’s an evolution with several variables that are kind of dictating the change.”

The variables occurred after the recession, which laid the groundwork for the Chromebooks, iPads and other forms of mobile technology.

A few years after 2008, the federal and state government focused on creating wireless networks within schools, said Britt. These networks were primarily federally funded through a Federal Communications Commission program called E-Rate. E-Rate works with schools and public libraries.

“The federal government said ‘we’re going to give you money to modernize your schools so that every class is connected,’ ” Britt said. “You have an expanded network connection.”

Around 2011, Google began making affordable, light-weight mobile laptops known as Chromebooks and a few years later these computers were purchased by SCS to help kids learn, Poplin said.

Schools like Chromebooks because they are cheap and easy to administer. And Google has seen its Chromebooks steadily saturate the U.S. school technology market since its inception. Google had a 59 percent share of mobile device shipments to U.S. schools in 2017, according to data from Futuresource Consulting.

It was the perfect digital wave: a growing wireless infrastructure funded by the federal government; affordable mobile devices; and the decrease in textbook funding.

“But it was the imperfect wave if you were a textbook fan,” Poplin said.

And many people still believe textbooks can be useful.

Glenda Gibson is a retired middle school English teacher and current SCS board member. She thinks textbooks can still serve a purpose, but it depends on the teacher and the learning styles of the students.

“The best learning modality is a blended approach” between textbooks and Chromebooks, said SCS Superintendent Jeff James said.

“As a teacher, it’s my job to adapt my teaching style to the learning style of the students,” Gibson added.

So if a certain class of students learn better with textbooks, then it’s the teacher’s job to adapt plans to fit their needs.

Gibson held onto three classroom sets of literature textbooks and found value with them as a beneficial tool to use in the classroom.

James is a proponent of every class having a set of textbooks to give the students more diverse learning options.

“One size doesn’t fit all” when it comes to the ways to teach kids, James said.

Castelloe and West Stanly High junior Nathan Brown are taking an AP Biology class where the teacher gave the students the choice to work out of a textbook or a Chromebook. Both Castelloe and Brown preferred the textbook.

Gibson always enjoyed the tangible nature of a printed textbook, where her students could physically hold the book while reading and highlight or mark important sections.

“I definitely find it easier to remember things when I read them in a textbook versus online,” said Katherine Pollard, a West Stanly junior. She specifically enjoys highlighting key points in the textbooks.

But Gibson acknowledges that it is not easy for textbooks to thrive in the digital age.

“It’s tough times for textbook authors and companies now that schools are focused on purchasing digital courseware,” she said.

But many students wouldn’t even know how to properly use a textbook for things like looking up a certain chapter in the table of contents, said Benita Long, a middle school science teacher in Cabarrus County Schools and friend of Gibson.

Textbooks are “a forgotten art,” Long said. “Kids today would view textbooks as a foreign language.”

West Stanly sophomore Rachel Efird, left, and junior Nathan Brown work on their Google

Chromebooks.

Rachel Efird, a sophomore at West, doesn’t recall ever using a textbook in middle or high school.

James believes teachers should show students what a table of contents is and how to look up indexes at the back of textbooks.

Students are relying more and more on a variety of different technologies to learn in today’s classrooms and that can come with a price.

The extended screen time students are spending on technology can be a problem, said Dawn Lucas, dean of teaching, learning and innovation at Pfeiffer University.

“A student’s technology is like their umbilical cord — it’s totally attached to them throughout most, if not all, of the day,” Lucas said.

Pfeiffer has intentionally focused professional development of faculty to include strategies for successful teaching of today’s super-connected students known as the “iGen.”

To better understand learners, Stephen Chew, cognitive psychologist and professor of psychology at Samford University, visited Pfeiffer last fall to discuss developing a mindset for successful learning with students, faculty and staff, Lucas said.

One takeaway from this opportunity, she said, was the importance of undivided attention when students are learning.

According to Chew’s presentation, the cost of distraction is high so anything, that draws attention away, including technology, hurts learning.

The brain needs about five minutes of refocus time, so it’s crucial when using technology as a tool in the classroom that teachers allow time for students to refocus their minds for the next task, educators said.

The students interviewed for this story admitted Chromebooks can be easily distracting because students too often play computer games or are on sites not permitted by the teacher.

When asked to choose between an updated textbook or a Chromebook to use for each of their classes, the four students unanimously chose the textbook.