CHAMPIONS OF STANLY: Albemarle builds modern football dynasty

Published 5:38 pm Friday, March 1, 2019

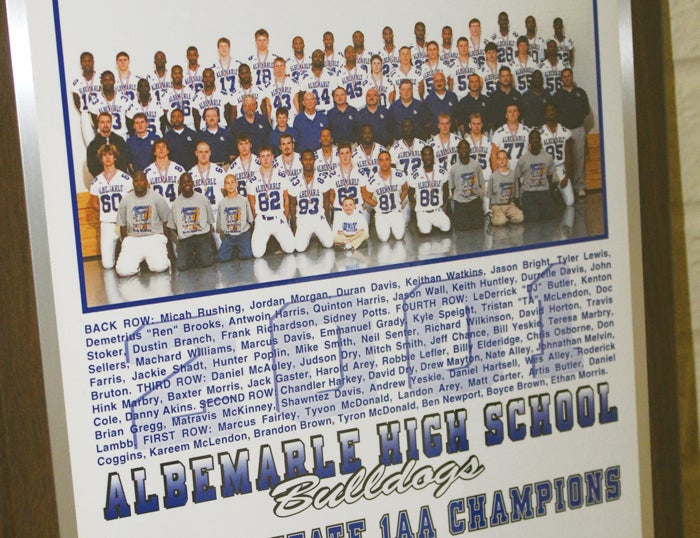

- The 2001 Albemarle football team was the first of the modern era to win a championship for the school. (Photo by Charles Curcio/staff)

Albemarle High School racked up 1-AA football state championships in 2001, 2002, 2003, 2009 and 2010. (Photo by Charles Curcio/staff)

The genesis of the five state championships Albemarle High School won in the 2000s started the previous decade.

In 1993, Albemarle was looking for several positions, including a principal as well as a head football coach.

Jack Gaster was back in school working on a school administration degree, having just coached at Lexington, while his top assistant, Baxter Morris, was working in insurance.

However, both continued to attend coaching clinics, including one at Lenoir-Rhyne College. The two found out about the Albemarle opening and decided to apply for the principal and coaching positions; they had previously decided, according to Morris, neither would coach football without the other one being on the staff.

Bill Church, superintendent at Albemarle City Schools, called Gaster to ask if he would become coach, but Gaster was wanting to become a principal, with Morris as the head coach. Church interviewed Gaster, then decided he wanted both in the athletic department, adding: “I can find a principal.”

After Church interviewed Gaster, the decision was made Gaster would take over as the Bulldogs’ athletic director and head football coach, with Morris as the assistant.

“We did everything humanly possible to get there early and get as many kids involved,” Morris said, noting in 1993 Albemarle was playing in a very competitive 2A Rocky River Conference including Forest Hills, Charlotte Catholic, Piedmont and others.

Participation was not a problem in 1993 for Albemarle, Morris said, adding the school had 105 kids come out to play football.

Morris said Gaster and himself were looking to build a long-term program based on discipline, which did not sit well with some kids at the time.

“We had to change the culture,” Morris said, adding of those original numbers about 15 players either eliminated themselves or were cut from the program.

Beyond the athletes involved, however, was the need for the community to be involved with the team. Morris said many of the students at Albemarle were descendants of parents who had been around Albemarle during the formative Toby Webb era and were “starved for winning.”

Morris added eventual success came out of the support of the community, including Roger Hudson and the Bulldogs’ booster club.

A second reason for the team’s successes in the future was the fact the team had good athletes like T.A. McLendon, who came to prominence breaking a career national rushing touchdown record before playing three seasons for N.C. State.

Continuity with the team’s coaching staff also was a big portion of success for the program. Morris was Gaster’s top assistant coach for the years Gaster coached the Bulldogs, along with assistants like Danny Akins, Antwain Hamilton and others who worked together for the better part of 15 seasons.

The first year Gaster and Morris came to Albemarle, another move which proved fruitful was forming relationships with the youth football program.

Players from an early age learned the verbiage and the plays which the high school team used, meaning when those players got up to the high school level, none had to learn or work in a new system.

One of the those players who was on the first team of young players was McLendon, which paid big dividends in his final year as a Bulldog.

The senior scored seven touchdowns and broke a national touchdown scoring record leading Albemarle to its first North Carolina High School Athletic Association state championship, the 1-AA title, in 2001.

Having a working relationship with a youth football program was something Gaster believed in, Morris said, adding Gaster had the ability to build a football program from the foundation up.

However, Gaster was not necessarily the easiest person with which to get along.

Morris said the former Albemarle head coach “was a strong personality; people got on one side of his or the other.”

Gaster was a player’s coach, Morris said, adding “the little things were the most crucial things…no player ever in the entire time there went on the field with dirty clothes on. They knew we cared; when we got the field ready, these kids knew it was the best we could give them. They saw how hard we worked…they had the best equipment to wear and got (the coaches’) best efforts in practice.”

One thing most can agree on in terms of Albemarle’s success during the Gaster years was the effectiveness of the Bulldogs’ offensive system, but it was not built overnight.

Morris said he and Gaster worked on that system for 25 years.

“We knew at Albemarle we would have to play teams better than us,” Morris said, adding some of the team’s famous plays were adapted from the Wing-T offense used by James Madison University in Virginia.

The team basically had three blocking schemes, whereas teams today use several times that number in games.

What Albemarle did well also, he said, was down blocking, meaning offensive linemen blocked at an angle into the center of the field.

Morris said the reason the team had such success was the players took ownership of their mistakes and wanted to work on those mistakes in practice.

“If something didn’t work right, they believed it was their fault…that they had not executed it right,” he said.

The success did not come right away as the Bulldogs were 4-6 in 1993, but that was the last season the team was under .500 in win percentage with Gaster.

In fact, Albemarle did not have a losing season from 1994-2005.

In his 11 seasons with the Bulldogs, Gaster was 121-25, winning 82.9 percent of his games including three straight 1-AA championships 2001 to 2003.

Albemarle also did not lose a game between Nov. 16, 2001 and Nov. 26, 2004, a streak of 50 games, ranking second all-time in NCHSAA history.

The team Albemarle lost to on both ends of the 50-game streak was Thomasville, the red-wearing Bulldogs whom won one less state title than the blue-clad Bulldogs in the period between 2001-2010.

When Gaster stepped down as coach and athletic director, little changed on the football team when Morris took over as head coach. The majority of the assistant coaching staff remained the same. Morris coached the team for six more seasons, leaving in 2009 after winning the 1-AA state championship with a perfect 16-0 record.

Danny Akins, another of Gaster’s assistants, took over in 2010.

Akins went 12-4 and won the school’s fifth 1-AA NCHSAA crown in his first year as head coach.

Morris said the legacy of Gaster and his proteges should be that “if you go into a place and do things the right way, treating the kids fairly but with discipline and making them toe the line…basically you can (win) in any situation.”

The former coach added he felt the players they coached wanted to belong to a part of something successful, and give them something positive with which to belong.

Nat Dunlap, the starting quarterback on the 2009 and 2010 championship teams, said he and his teammates from those successful squads were around 7 and 8 years old when players like Jordan Morgan, Keith Huntley and T.A. McLendon were winning state championships.

“There was an understanding we were going to be one of those guys. When we got there, we carried out what we had known for a decade we were going to do,” Dunlap said.

With his teammates, like 2010 finals MVP A.J. Little at running back, the cohesiveness the players had on the field came from time spent on the practice field and off the field.

Those players were competitive with each other about everything, whether it was who could eat the most pizza at the cafeteria or pickup basketball games in P.E. classes, Dunlap said.

“(The players) grew up ultracompetitive from a young age, learned the system. Everything meshed together for us,” Dunlap said.

Competition between the players was “ferocious,” he said, with “feisty guys that hungered to win” and it rose to “pride on a whole other level” especially with football, which Dunlap called “a gladiator sport.”

Beyond competitiveness between players on the Bulldogs, though, the players felt a responsibility to each other to perform well on and off the field, Dunlap explained.

“I’m not going to put my head down on my pillow knowing I let my brother down if we lost,” Dunlap said.

The responsibility of continuing the school’s winning traditions was no more evident to Dunlap than when as a freshman in 2007 the team got a pregame peptalk before its third-round playoff game at West Montgomery.

That season, the Bulldogs had risen above preseason expectations to reach the playoffs to face a Warriors team Albemarle had lost 41-7 to earlier in the season.

McLendon talked to the team and became so excited he ripped his jacket off; as he did, the zipper cut open the forehead of Charlie Coggins “wide open,” Dunlap recalled.

Trainers wrapped up Coggins to the point he looked like a mummy, according to Dunlap, but he went ahead and played.

The emotion of that pep talk, Dunlap said, imparted to all of the players a sense of the culture of the program and how much it meant to those who had played before him and his teammates.

That night, West Montgomery won a much closer game over the Bulldogs that season, 13-7, and went on to play in the state finals, losing to Kenan. But the lessons from that season stuck with Dunlap and his teammates.

Football, Dunlap said, brought together players from different aspects of life and united them for a common goal, regardless of their race, social standing or other differences. Playing for Albemarle in those days, he said, meant you were part of a brotherhood.

He illustrated that aspect of the team with a story about a game his senior season.

Albemarle had to forfeit three games from earlier in that season, which put the Bulldogs on the road in the first round of the state playoffs at Bishop McGuinness.

The Bulldogs trailed late in the game facing a fourth-down situation. A punt would probably have ended Albemarle’s season.

On the sidelines during a timeout, Akins asked Dunlap what he wanted to do. The quarterback said he wanted the football in his hands.

Akins did just that, calling a bootleg pass for Dunlap, who found tight end Corey Dick for a long touchdown pass. Albemarle went on to win 27-14. It won the state championship weeks later.

On the bus after the Bishop game, Montego Baldwin, a defensive back, came up and sat down beside Dunlap. The two did not share much in common outside of school, Dunlap said, but they were both part of the football brotherhood.

“Montego sat next to me and said, ‘I live for stuff like this.’ He saw something in me, that fire in my eyes,” Dunlap said. “He said to me, ‘I would do anything for you in my life. My number will never be deleted from your phone.’ ”

The idea of family and brotherhood surrounding the team was also fostered by Morris and the assistants, Dunlap said, adding the players had friendships with the coaches.

“We knew we could sit down and talk with them about whatever,” he said. “On Friday nights, you will listen and respond to (coaches) if you have a relationship with them.”

New coaches who came to the team, like former Albemarle athletic standout Eddie Wall, were also welcome additions, Dunlap said.

Even though he never was in one practice with Gaster, Dunlap said he felt like he had been coached by him because of the program he had put in place with Morris, Akins and the assistants who meant so much to the players.

“He didn’t coach any of us, but he left his mark on us.”