SALUTE TO SERVICE — ‘This is so new, I feel like a first-year teacher all over again’: Teachers adjust to remote learning

Published 4:06 pm Tuesday, June 2, 2020

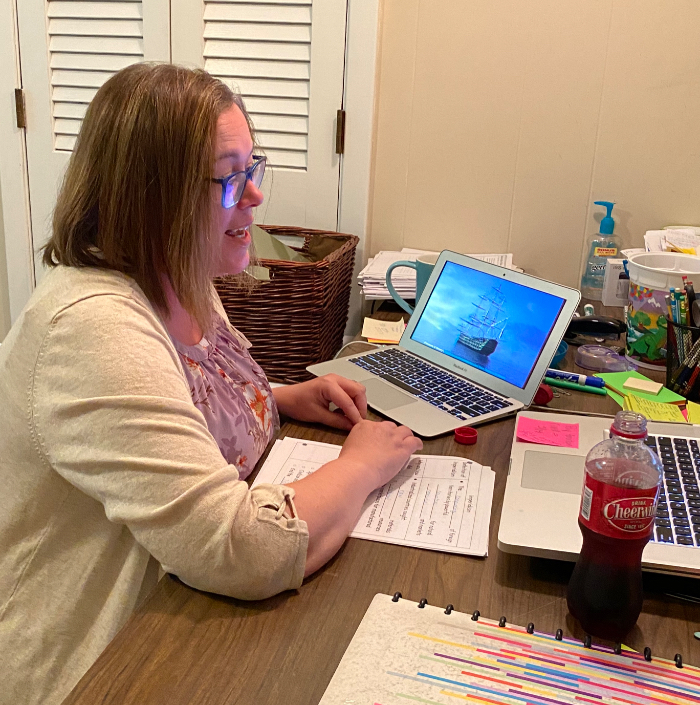

- Albemarle Middle School teacher Angela Almond chats with her seventh grade students on Google Meet. Photo courtesy of Angela Almond.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The coronavirus pandemic has impacted people from all parts of society. One group that has been hit especially hard is teachers, who — in a short period of time — had to transform the way they interacted with and taught their students.

Angela Almond is an educator who has been teaching longer than her seventh-grade students at Albemarle Middle School have been alive. But nothing in her 16 years with Stanly County Schools could have prepared Almond, 42, for the pandemic and the life-changing ripple effects it’s caused for school systems and teachers around the country.

Though her principal sent an email to staff March 13 warning of the possibility of school closures, it wasn’t until Almond received an email from Superintendent Dr. Jeff James that weekend that her fears were confirmed: All public schools across the state were closed for two weeks, per an executive order issued by Gov. Roy Cooper.

All the comforts she had known for 16 years as a teacher were suddenly, in one fell swoop, ripped away from her.

“My heart dropped into my stomach and there were a lot of tears shed that weekend,” she said upon learning the news. Every time Cooper extended the order, more tears were shed, Almond said.

Cooper eventually made the move to close schools for the remainder of the academic year.

James said the school system had already been preparing for remote learning. The school system introduced virtual learning opportunities during the February school board meeting to help combat loss of instructional time due to inclement weather. But SCS was likely not prepared for a pandemic that has forced schools to close for months.

For Susan Haltom, a first-grade teacher at East Albemarle, the school closures meant she would be prevented from interacting with her students at a critical time when they really start to understand key concepts, especially reading comprehension.

“The time of year that the pandemic happened is usually when a lightbulb really goes off with all our kids and they’re starting to really grasp all the concepts,” said Haltom, 54, who has taught in the school system for 30 years, including 17 at East. “And it was like, ‘Oh no, I’m not going to be there to really make sure those concepts are grasped the way they naturally come during a regular school year.'”

Almond said the students were still stunned when they briefly returned to school to get their belongings and Chromebooks — not knowing when they would come back.

“I think everyone was in shock that first week,” she said. “We didn’t know what to expect and this was something we never had to do.”

“This is so new, I feel like a first-year teacher all over again,” she added.

Adjusting to a new normal

Though the school buildings may be closed, teaching and learning is still happening around the county — just virtually from the safe confines of individual homes.

Each morning, Almond, who teaches English and social studies, sends an email to her 43 students, detailing assignments and class reminders along with any individual student achievements she wants to highlight. She also sends weekly, personalized emails to each student to check in on them and make sure they are okay.

She teaches class from 1 p.m. to 2 p.m. Monday through Thursday through the videoconferencing tool Google Meet. After class, she often gives students some time to virtually talk and interact with each other.

Albemarle Middle School teacher Angela Almond interacts with her class on Google Meet. Photo courtesy of Angela Almond.

Almond said it took some time initially to convince students that even though they were at home, they were still in school and would still have to complete assignments and virtually show up for class.

Almond has done her best to adjust to this new world, but it hasn’t been easy.

“It’s a very strange feeling” working remotely, she said. “It’s like I’m constantly questioning myself because I’ve never done this before. When I was in the classroom, I knew 100 percent what I was doing and the next steps to take.”

Many of Haltom’s students have struggled to understand why they are at home instead of school each day.

“Home is their place where they eat and sleep and have family time and play; it’s not school and that’s what it had to turn into,” she said.

Each of the first-grade students are completing work packets, though Haltom, along with her first-grade colleagues, have created weekly YouTube videos for the students to watch. Haltom’s videos focus on the phonics-based program Letterland and she incorporates her two dogs, Duke and Bean, which the students enjoy. Each video lasts around 10 to 20 minutes.

“I never thought I would ever do something like that,” she joked about becoming a YouTuber. Luckily she has a teenage daughter who has helped her film and upload the videos.

East Albemarle first-grade teacher Susan Haltom has made educational Youtube videos for her students with help from her two dogs, including Bean. Photo courtesy of Susan Haltom.

She also calls the parents each week to get updates about the students and make sure all is well. Haltom has gotten to know the parents on a level she hasn’t before and likely would not have if not for the pandemic.

“They let me into their lives as far as what’s going on,” she said.

She has told her class that students all across the country are also learning from home.

“We just have to be safe,” she tells them, “and to be safe we need to stay home.”

Since standardized end-of-grade tests have been canceled, Almond has had the flexibility to incorporate more student-driven instruction. She gauged her students about their interests and what they wanted to learn and has tailored her curriculum to best suit their ideas. Her students are currently learning about Greek mythology in ELA class and World War I in social studies.

“Really letting the students drive your instruction, that’s been a huge game changer for us during this,” Almond said, “and I think that’s something I want to do when we start back.”

Lack of internet a problem for some students

Almond said a common problem teachers are facing is that some students don’t have reliable internet — if they have it at all — to complete the assignments and attend virtual class.

Teaching in Albemarle, “you would think everybody has access, but they don’t so that’s been a challenge,” Almond said, noting it’s likely even more of a challenge for teachers in more rural areas of the county.

Superintendent Dr. Jeff James said according to school data, around 10 to 12 percent of students in the county have connectivity issues, which makes completing online assignments difficult. He said the school system’s information technology department is working with several providers, including Windstream, Spectrum, Conterra and Verizon, to try and address the issue.

Though Almond has a 95 percent participation rate in terms of kids attending class and completing assignments, which she says is “really high,” and almost all of her students have access to key resources, she has had to work with one student who has no access to reliable internet.

Almond worked extensively trying to help the student find reliable internet access, including utilizing WiFi hotspots in her area. Fortunately the student’s sister has internet, so she spends a few hours per day completing assignments at the sister’s house.

“We’re lucky because we were able to find a solution for her, but that’s not always possible,” Almond said, adding that lack of internet access is an issue the community needs to examine and work to address.

Haltom said she also has students who lack internet. She and the other first-grade teachers have emphasized to parents that though the videos are instructive, the work packets are most important.

Time to slow down

Working from home has allowed Almond time to slow down and “appreciate things a little more.” She has been able to spend more time with her son, who’s in middle school. Her husband, who’s a barber, has also been at home.

She said as a mom, it’s been easy for her to give “grace” to her students for a missed assignment or if someone forgets to attend class “because I see what my family is going through and I know that we’re not the only ones.”

While the pandemic will deprive many teachers of likely being able to physically hug and say goodbye to their students when the academic year ends, it will be especially hard for Haltom, who is retiring at the end of the school year.

“I won’t get those last final goodbyes with those kids,” Haltom said, noting it’s not just her current class but the other students she’s taught in the past.

Though teachers have struggled at times to adjust to the new reality of remote learning, James is proud of them.

“Our teachers have been phenomenal,” he said. “I don’t think anyone in our community can doubt that our teachers are doing this because they love kids and it’s a calling.”