From Laos to Albemarle: Ly lives American Dream

Published 4:19 pm Wednesday, November 24, 2021

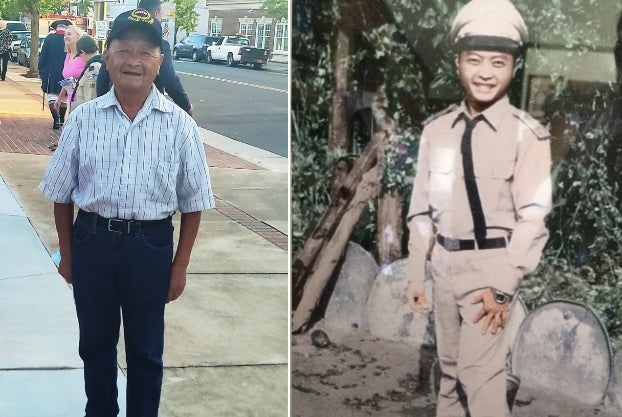

- Xang Ly spent about 14 years helping American forces during the Vietnam War before he and his family moved to Albemarle. Photo courtesy of Nhia Ly.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

For Veterans Day this year, Albemarle resident Nhia Ly took to Facebook to make a special post about his father, Xang, who fought alongside the American forces in the so-called Secret War inside Laos, a vital but little known part of the larger Vietnam War.

“Thank you for your service and carrying me on your back!” he wrote.

Throughout most of the 1960s and first half of the 1970s, Xang Ly served as a captain with the Special Guerrilla Units or SGU, where he risked his life to assist U.S. forces in neighboring Vietnam.

He is part of the Hmong, a term meaning “free people,” which is an ethnic group originally from southern China but whose population now lives throughout much of Southeast Asia. Nhia estimates there are between 300 to 400 Hmong living in Stanly and Montgomery counties, most of whom, like his family, originated from Laos.

Even with a robust population spread throughout the county, many Stanly residents still know little about the Hmong people or the heroism displayed by veterans, such as Xang Ly.

“When you tell them about the Hmong people, they have no clue and they’re often like, ‘Where are you guys from?’ ” Nhia Ly said.

Once the war ended, Xang Ly and his family traveled to Thailand before eventually resettling in Albemarle. Though he knew no English, Ly worked a variety of jobs to provide for his family.

He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1984 and later served as president of the N.C. Chapter of the Lao Veterans of America, Inc. He is married to Kia and they have four children, including Nhia, who works for the City of Albemarle and owns Ly Cuisine with his wife Zoua.

In many ways, Ly, 79, is the embodiment of the American Dream: Someone who immigrated to the country with little resources yet through hard work and determination, has been able to carve out a successful life not just for himself but for his family.

As appreciation for his service and what he has meant to the community, the City of Albemarle recently selected Ly to serve as its grand marshal for the Christmas parade this weekend.

“We wanted to recognize Mr. Ly’s service to our country as a veteran of the Vietnam War and his journey to become a resident of our city,” said Main Street Manager/Albemarle Downtown Development Corporation Director Joy Almond of the city’s Special Events Committee choosing Ly. “We also wanted to show appreciation to Mr. Ly and his family for their contributions as outstanding citizens of Albemarle, and we are honored to have him lead the parade procession this Saturday as grand marshal.”

Ly said he was “very happy, honored and humbled” to be chosen. Since Ly has some trouble communicating in English, Nhia and Zoua helped translate for him in an exclusive interview with The Stanly News & Press.

Xang Ly and his son Nhia look through old newspaper articles and photographs.

Fighting alongside the Americans

Xang Ly grew up in Laos as an orphan and though he never directly attended school, he often stood outside classrooms, trying like a sponge to absorb as much knowledge as possible. In this way, he was able to learn how to read and write, something that was relatively rare in the impoverished country. He held several jobs, including working on rice farms and laundering clothes.

Concerned that Laos would fall into Communist control, Central Intelligence Officer James Lair, who was stationed in Thailand and serving in the Special Activities Division, met with Hmong military leader Vang Pao in the late 1950s to recruit Hmong soldiers to fight against Communist forces. With the CIA’s help, Pao raised an army of around 30,000 guerrilla fighters to fight in the Laotian Civil War, also known as the “Secret War,” between the country’s Communist party and the Royal Lao Government. The soldiers became part of the SGU.

The SGU’s duties included blowing up the enemy’s supply depots, ambushing supply lines, trucks, mines and attacking enemy strong holds. The SGU also played a critical role for the CIA in rescuing American pilots shot down flying into Laos from North Vietnam.

Since sending in American troops to Laos would have violated the 1954 Geneva Accords, which declared Laos an independent and neutral country, the United States had to engage in covert operations.

“They didn’t want Southeast Asia to be overrun with Communists,” Nhia said about the CIA working with the Hmong population. There was another motive, he said: By creating a proxy force in Laos, America could better observe and protect the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a logistical network that ran from North Vietnam to South Vietnam through Laos and Cambodia, and which provided key support to the Viet Cong, the Communist military group which fought against U.S. troops.

Ly was one of the many soldiers trained by Pao, whom he knew personally, to help assist the Americans in their mission to stop the spread of Communism in the region. He also spent a few weeks at a training camp in neighboring Thailand.

Only in his early 20s at the time, Ly served as a logistics officer at the Long Cheng military base, where he helped distribute key military supplies, such as rice and guns, which were airdropped by Air America, a CIA-owned airline. These were then sent to Hmong soldiers in Laos and stationed in North Vietnam.

Working alongside the Americans empowered many Hmong, who were not necessarily used to kindness from others.

“We have always for centuries been prosecuted, but for the first time here are these ‘tall giants’ (term used to describe the Americans)…that came to the country and all of a sudden we’re being given food, which no one has ever done that for us before,” Zoua said.

He also was involved in many scouting expeditions. During one such mission in the late 1960s, a small group of soldiers, including Ly, traveled into North Vietnam, where they pretended to be part of the Viet Cong to engage in a search and rescue mission to locate fallen American pilots and bring them back to Laos.

To avoid being confused with enemy combatants, the Hmong soldiers had a unique way of conveying to the Americans that they were allies. Since they could not speak English, Ly and his fellow Hmong soldiers, after discovering a pilot, tossed in his direction a canteen that had a USA symbol on it, Zoua said.

“We were very happy to find the fallen pilot and bring him back to Long Cheng air base,” Ly said.

For much of Ly’s time during the war, he was vulnerable to enemy attacks. Nhia mentioned his father was shot down many times while trying to distribute aid. During one supply mission into Vietnam, his helicopter was attacked by Viet Cong, killing two soldiers, including the pilot. Shrapnel from one of the attacks is still embedded in Ly’s head.

“He’s got like nine lives,” Nhia said, noting his father never thought about dying or had any concerns for his safety. “He was focused on his mission of helping the Americans.”

As a result of helping the CIA-sponsored Secret War, more than 35,000 Hmong-Lao SGU soldiers were killed, according to an online history of the conflict, presented by the Special Guerrilla Units Veterans and Families of USA, Inc.

Leaving Laos and finding a home in Albemarle

In the spring of 1975, once the Communist party overthrew Laos’ royalist government, Ly and his family — his wife Kia, Nhia, daughter Bouasy and son Pheng — along with thousands of other faithful Hmong soldiers who were promised sanctuary, showed up at Long Cheng base expecting to be airlifted, but only a small number were evacuated.

“You’ve got all the families at the airfield waiting to get on board…and that day only one airplane showed up,” recalled Nhia, who was around 5 at the time. Similar to what took place a few months ago with the evacuation of civilians from Afghanistan, many Hmong were desperately hanging onto the plane, even as it was taking off.

Ly and his family decided to leave Laos on their own. They traveled by night and hid in the daytime to avoid capture. After trekking through dangerous jungles and making the treacherous cross of the Mekong River, the family was smuggled into Thailand, Nhia said. They were placed in a refugee camp, where Ly’s family stayed for many months before the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service (LIRS) helped resettle the family in Albemarle in August 1976. Christian agencies provided much of the assistance to Southeast Asian refugees like the Hmong people during this time.

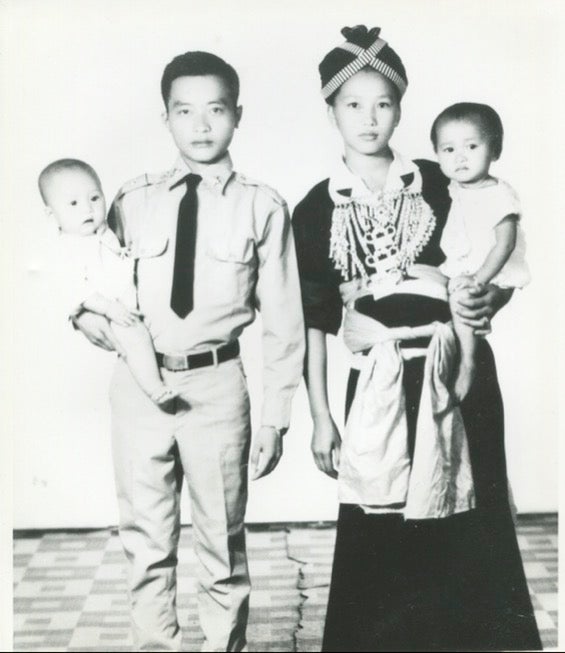

Xang Ly in Laos in the early 1970s with his son Nhia, wife Kia and daughter Bouasy. Photo courtesy of Xang Ly.

Though Ly and his family were safe from the violence in Laos, they knew nothing about the United States, nor did they speak English.

Once they arrived in Albemarle, after traveling almost 9,000 miles, First Lutheran Church provided them with a house and had a job at Collins & Aikman lined up for Ly. Nhia and Bouasy enrolled in eighth grade at New London Elementary. Two months later, in October, the family expanded when Nhia’s sister Hmong Gao was born.

“It was overwhelming for us, but honestly it was good overwhelming,” Nhia said about the new environment, adding that his family had a stable life complete with everyday items most Americans take for granted like a refrigerator, television, food, shoes and a car.

The First Lutheran congregation also took the family under its wing, which helped make the adjustment period a little easier.

“That’s the reason why we haven’t moved anywhere else because the church family has been so good to us,” said Nhia, whose family is still part of the church.

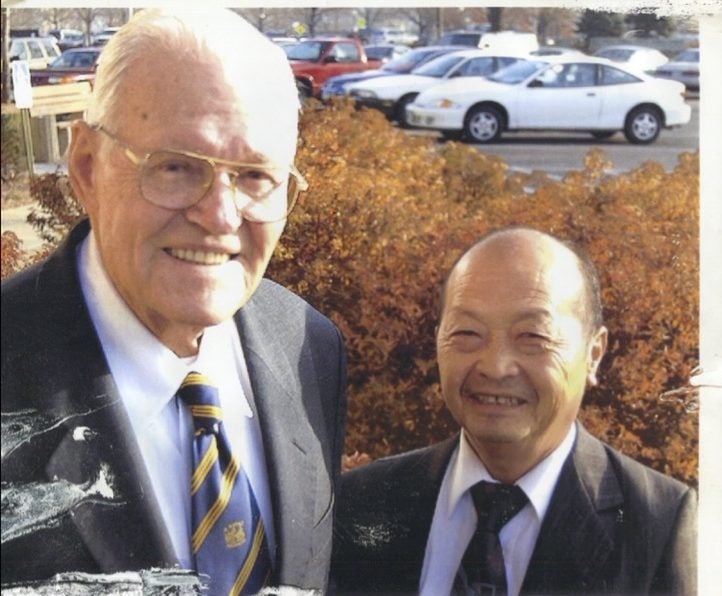

During the 1980s, Pao visited Albemarle and spent time with Ly and his family at their Albemarle house, which meant a lot to him. Ly has also met Lair, the CIA officer who worked with Pao to kickstart the Secret War.

Xang Ly with former CIA officer James Lair, who played a pivotal role in working with Gen. Vang Pao to train the Hmong. Photo courtesy of Xang Ly.

After working at Collins & Aikman for about a decade, Ly was employed as a custodian for First Baptist Church before opening up a shoe business called Ly Corporation, which employed around 50 people and specialized in making cowboy boots for companies like Walmart and JCPenney. He later operated an Asian market before retiring in 2018.

Ly has never returned to Laos since leaving almost 50 years ago, but there is a specific reason for that. As part of the SGU who fought against the spread of communism, his name is included on the country’s blacklist and he is prohibited from coming back to the socialist country.

Nhia recently purchased a brick paver for his father as part of the Charters of Freedom display near Albemarle City Hall to honor his service with the SGU.

“What he’s contributed to the service, I think at least for him and his generation, they need to be recognized and commended,” he said.

During the dedication ceremony in October, Nhia tried his best to translate the speeches, writing on Facebook afterwards that his father “understood it well from his emotions. He was in tears.”

- Xang Ly shed tears during the Charters of Freedom dedication in October. His son Nhia purchased a brick paver to honor Ly’s service.

- Nhia Ly purchased a brick paver for his father to honor his military service. Photo courtesy of Nhia Ly.

Growing up in a war-torn country beset with chaos, violence and political instability, Ly and his family hold a deep appreciation for the freedom that comes with living in the United States.

“You have to protect it, nurture it, appreciate it and don’t take it for granted,” said Zoua, whose family also came from Laos.

Even though Ly, Nhia and the rest of the family will always be proud Hmong-Lao and do their best to promote their heritage, there is only one place that they call home.

“Home for us is here in Albemarle,” Nhia said.