‘I believe we are all superheroes’: Stanly native works to empower residents, preserve historical landmarks

After recently seeing the newest Marvel movie “Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania” with his daughter, Dion Brooks’ biggest takeaway was this: No matter how small you are, you can still accomplish great things.

“I believe we are all superheroes,” Brooks said.

Although people don’t possess superhuman powers, “you do have an inner-self, you do have something within you,” he said. “You can make change, but you have to believe in the change and believe you can do anything.

“I believe everyone has some type of power, like your God-given gift,” he added. “It’s just up to you to figure out what it is and how you can save the world with it.”

While Brooks might not be saving the world, he is making a lasting impact in his community. He has been working to preserve landmarks associated with Stanly County Black history, especially within the South Albemarle area, through his nonprofit organization Stanly Avengers, which was founded two years ago.

Brooks has been working with many people associated with Stanly Avengers, including vice president John Anderson III.

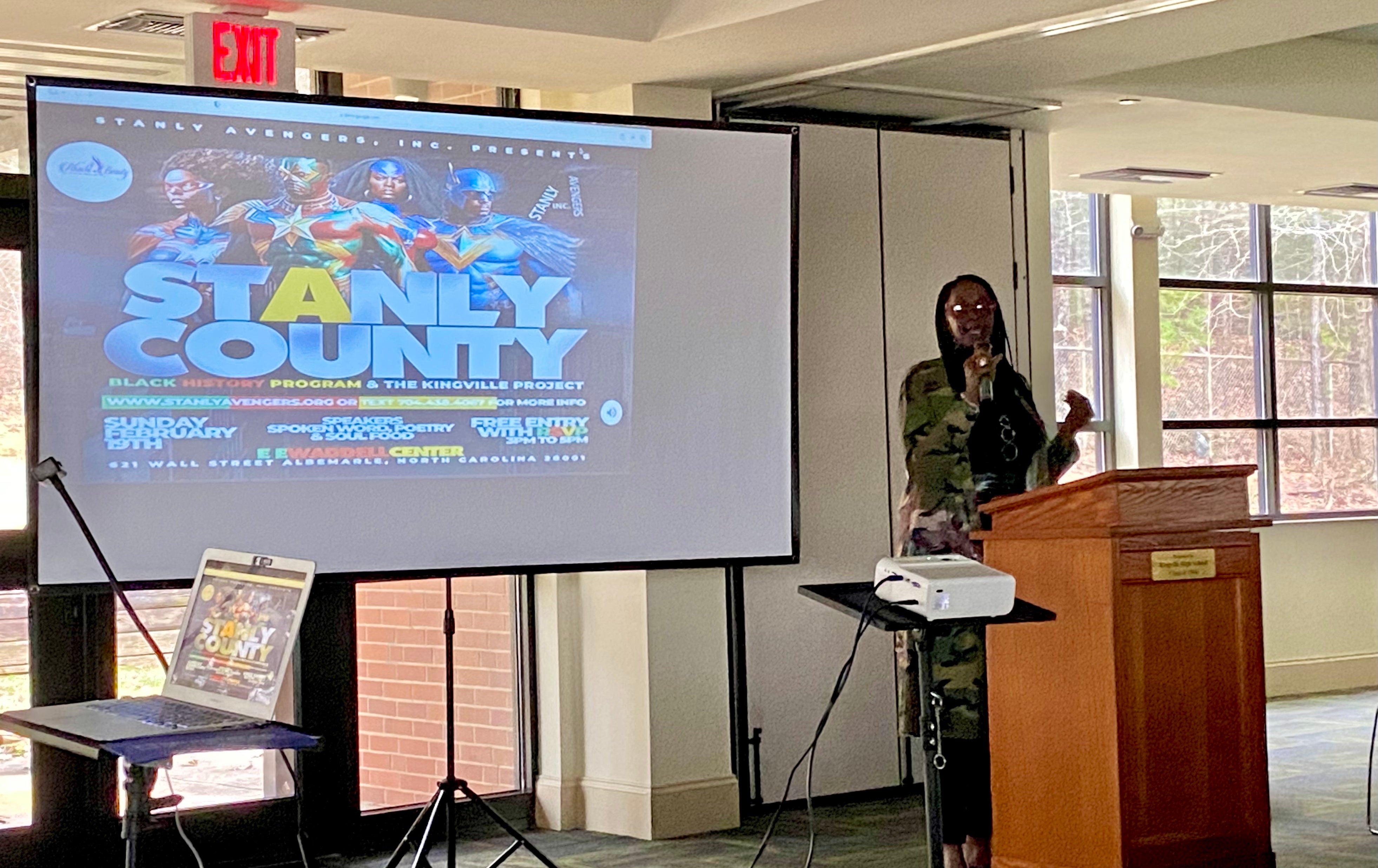

Francine Young talks about the Stanly Avengers.

“It’s empowerment that we have to put into the community,” said Anderson, who operated a clothing store in downtown Albemarle called Harlem World and ran for City Council in 2011. “It’s up to us to give back to the community.”

With many obstacles, including economic distress and high levels of crime in certain areas, an organization devoted to improving the community is more important than ever, Anderson said, noting Stanly Avengers has already applied for multiple grants.

“We are the Avengers and we have taken that upon ourselves to be those people who change our community,” Anderson added. “And it’s going to take a united effort to do that.”

Stanly Avengers has seven board members and close to 70 people are part of the organization’s private Facebook page, Brooks said.

Stanly Avengers plans to have several workshops this year to talk about issues such as prison reform and second chance employers, financial literacy and real estate, generational wealth, black mental health and S.T.E.A.M. (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics) Education.

Brooks wants to see more people become involved in their community and become S.U.P.E.R., which stands for support, uplift, promote, educate and repeat.

The Kingville Project

During the second annual Stanly County Black History Program at the E.E. Waddell Community Center Sunday afternoon, Brooks spoke about the Kingville Project, a three-pronged campaign to conserve, preserve and celebrate key landmarks that help connect generations of Black residents to their past.

The idea for the project came last year when he was talking with a white friend while traveling through a South Albemarle neighborhood. The friend confused the Amhurst Gardens community with Kingville.

“I said, ‘Don’t tell anyone else that you don’t know the difference between Amhurst and Kingville,’ ” Brooks said. “So it made me think: Who else doesn’t know the difference?”

After some basic research, Brooks learned Kingville was an unincorporated community in the southern part of Albemarle — and then he was off and running, learning more about the community in order to educate others.

Brooks and the organization are trying to raise money to erect 10 historical preservation markers throughout Stanly County. There will be six markers honoring The Rosenwald Schools in Kingville, New London, Oakboro, Porter, Norwood and Cottonville. The other four markers will honor the Kingville Community, Kingville Park, Kingville School and Dr. Ogden King.

Brooks set up a GoFundMe account in November with the goal of raising $20,000 to help pay for the historic preservation markers.

He was scheduled to speak before Albemarle City Council Monday night about the Kingville Project and his push to recognize the historical landmarks.

Brooks and many volunteers have helped cultivate civic pride by working to beautify several Black neighborhoods through the Adopt-A-Street Community Cleanup campaign which began last April. Stanly Avengers has adopted roughly 20 streets so far including Wall Street in honor of Kingville.

Just because many younger people were not around during the time of Kingville High School and Kingville Park, for example, does not mean they did not exist and should not be preserved, remembered and celebrated, he said.

“I just want to, like a movie, reboot Kingville and give it its identity back,” Brooks said.

Part of that momentum includes celebrating the 125th anniversary of Kingville, which was officially named after Dr. Ogden King in 1908, shortly after his death.

Informing people about Stanly’s Black history

As part of Stanly Avengers, Brooks works to educate the community, especially Black residents, about their history so they can understand where they came from and feel more empowered to preserve the legacy.

“It’s really about self-identity, because I feel like if you don’t know who you are, you will not know where you’re going,” said Brooks, who was donning a white T-shirt emblazoned with a giant “A,” representing the Avengers.

Dion Brooks founded Stanly Avengers two years ago.

As part of Sunday’s program, which began with the singing of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the Black National Anthem, Brooks and other members of the organization spoke of the history of several landmarks and the leaders associated with them. Among the highlights:

- Kingville was named after Dr. Ogden King, a white physician who practiced medicine in the city in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He showed such concern for the Black community, even helping to build a church, that when he died in 1908, the community took his name.

- The Rosenwald Fund, established by Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington, provided grants to Black communities across the country to improve education, often by building schools. The funds assisted more than 800 projects in North Carolina, including several schools in Stanly County.

- Kingville School, which received funds from Rosenwald, was around in the beginning of the 20th century and eventually changed its name to Stanly County Training School. The earliest known reference of a Black school in Albemarle, it was likely located on Lundix Street and later was sold by the Board of Education.

- One of Stanly County Training School’s noteworthy principals was Horace C. Goore, who would later serve as principal of Kingville High School, which was built in 1936. Goore was the principal at Kingville from 1932 until 1944. He was followed by Dr. Elbert Edwin “E.E.” Waddell from 1944 to 1963 and Baxter K. Williams from 1963 to 1968.

- Kingville High, which is now the Waddell Center, is located along Wall Street, named after William Henry Wall, a community activist and brick mason who helped build many homes on the street. He also taught Black students brick masonry at the school during the evenings.

- Brooks’ mother LaBonnie Knight was the first Black cheerleader at Albemarle High School during her senior year in 1970-71, following integration a few years earlier.

Dion Brooks with his mother LaBonnie Knight. Photo courtesy of Dion Brooks.

Brooks recognized Charles Crump, 90, one of Kingville High’s 1949 graduates. He briefly spoke about the school’s impact on his life.

When Black students wanted to pursue higher education, Waddell “would go all out to see that you attended college,” Crump said, noting Waddell helped get him into Winston-Salem Teachers College, now Winston-Salem State University, and even introduced him to the school’s president.

Comparing his organization to a ship, Brooks told the crowd some people might get on and off, but that is okay, as the ship will continue progressing forward.

“This ship is going to move regardless,” he said. “It’s going to keep sailing, because I’m on a mission.”