Tidus Stanback looks back on career, historic turn as first Black Albemarle council member

He served in Vietnam, met well-known luminaries as a Greyhound driver and broke barriers as the first Black person to serve on the Albemarle City Council.

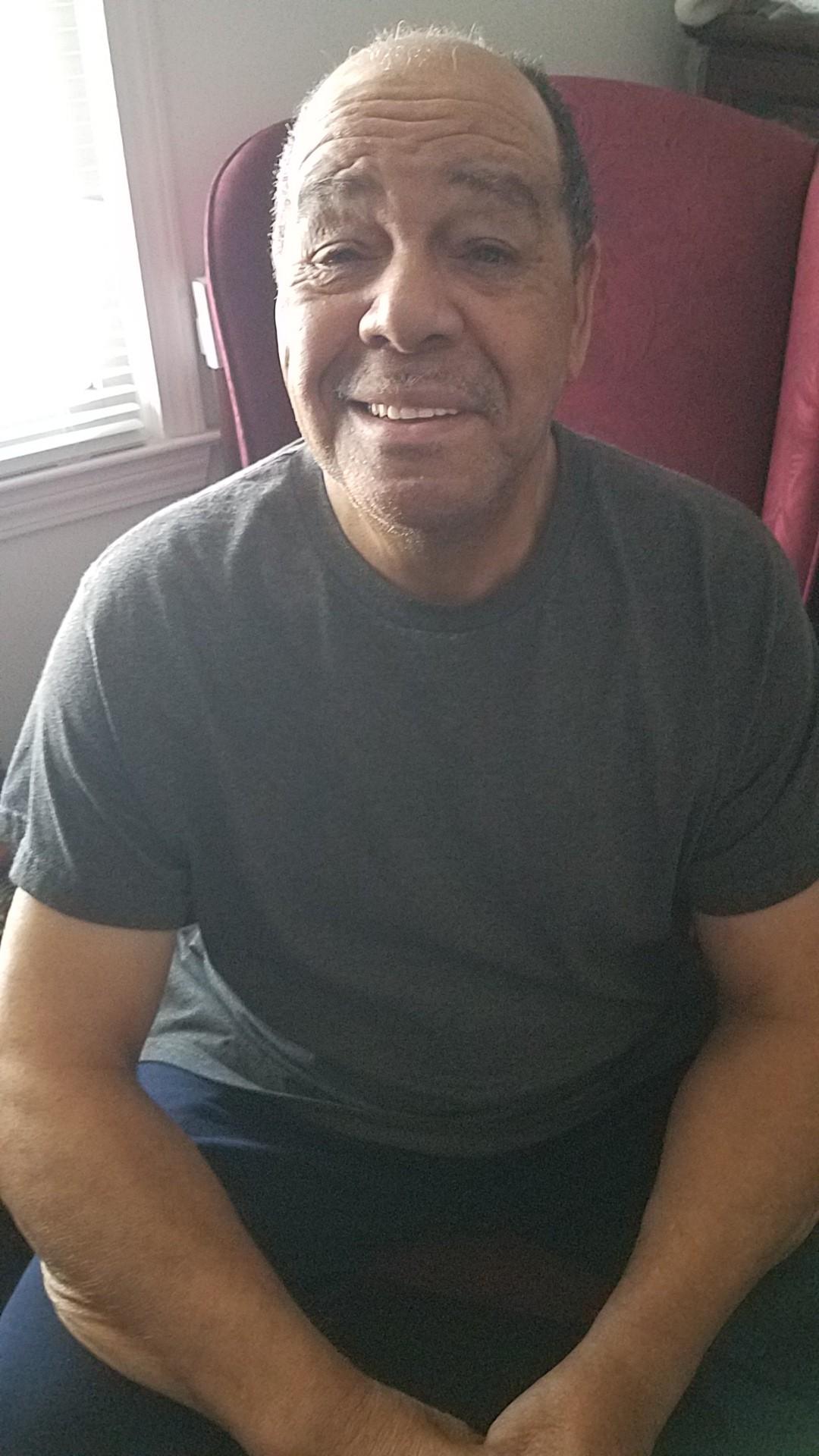

Tidus Stanback, 80, has done a many things during his life.

“I am proud of it,” Stanback said regarding his seven years on the council from 1988 to 1995. “But I don’t boast about it. I just did the best that I could do.”

His history-making election paved the way for other Black leaders to have a seat at the political table. Others serving on the council included the late Tim White, who was on the council from 1995 to 2008, and current councilman Dexter Townsend, who has served since 2009.

“I’m very fortunate for the road that Mr. Stanback paved for others to follow, not just me personally but for future generations to come,” Townsend said, calling him a “strong resource and advocate” for the community. He said he still occasionally leans on Stanback, who he has known for more than 30 years, for advice and counsel.

“He started paving the road, but we have got to continue that progress,” Townsend added, noting his goal is eventually for a Black resident to serve on the Stanly County Board of Commissioners. “You need diverse opinions on everything.”

Tidus Stanback, second to the right in the back, with the other Albemarle City Council members. They include, from front row: Judy Holcomb, Roger Snyder, Mayor Troy Alexander; back row: Jane Hartley, Jimmy Napier, Roy Talbert, Stanback and Jack Neel. Photo courtesy of Brenda Stanback.

Originally from Montgomery County, Stanback moved to Stanly when he was a young child. He graduated from Kingville High School, where he achieved athletic success playing basketball and as the quarterback for the football team.

He particularly enjoyed many battles against Kingville’s rival, West Badin High School. Several trophies of the school’s athletic prowess are on display at the E.E. Waddell Community Center.

Stanback spent a few years at Livingstone College in Salisbury before enlisting in the U.S. Army. He spent about a year and a half in Vietnam during the war.

Following his time in the service, Stanback drove for Greyhound, where he traveled across much of the country.

“It was really great for us because we had the opportunity to meet an awful lot of prominent people,” his wife Brenda James Stanback said.

She noted her husband often drove NBA teams from their hotels in Charlotte to practices, “and he always asked permission for us (including their son) to attend.” He met pro athletes such as Kurt Rambis, Kevin Johnson and Kenny “Sky” Walker, and singers such as Patti LaBelle and Tina Turner.

A high honor during Stanback’s 32 years as a driver was when he led a caravan of vehicles when former President Ronald Reagan came to Charlotte. Stanback received a pin from Reagan, his wife said.

“I liked him as an individual,” Stanback said, noting Reagan seemed to be “very down-to-earth.”

Another notable moment was when Stanback met Nelson Mandela in Atlanta, shortly after the South African president was released from prison in 1990.

An active presence within his community, Stanback purchased a school bus to shuttle young kids around to places like Morrow Mountain State Park.

Stanback also operated a convenience store known as the Kingville Mini-Mart.

“He made himself known to the community by the good deeds he was doing,” Brenda said.

Tidus Stanback got involved in politics in the 1980s after already being a well-known figure within the South Albemarle community. Photo courtesy of Brenda Stanback.

Stanback’s first foray into local politics was when he served as president of the Stanly County Chapter of the NAACP in the 1980s. He said he got involved because he wanted to make a change within his community — especially when it came to district representation in the city of Albemarle.

In January 1987, Stanback and the local NAACP asked the city council to switch from its at-large elections system to a district representation system, contending the at-large voting system discriminated against Black candidates.

Black residents had previously run for seats on the city council, “but there was just no way that we could elect anybody,” Brenda said. “We were outnumbered.”

When the council voted later that year to not adopt such a system, the NAACP sued the city. It took several months, but in January 1988 the city resolved its dispute with the NAACP.

As part of the agreement, the city was divided into four districts, with one council member representing each district, along with three at-large districts. The new system allowed Black residents to have representation as part of District 1, which encompassed the South Albemarle area.

“It was back during the time when still a lot of people would not speak up themselves and he had no problem doing it,” Brenda said about her husband leading the effort to secure more representation.

Stanback acted as a calming force and helped keep the Black community grounded while the lawsuit was still being decided, Brenda added.

“He kept impressing upon us the need and the importance of going ahead and sticking with it.”

Having been such a visible figure within the South Albemarle community, it made sense Stanback was the one to represent District 1. He won the election in 1988, making history as the first Black person to have a seat on the council. He resigned from his post as NAACP president after the victory.

“Somebody had to run and it was not something that was forced on me,” he said. “I wanted to run.”

Brenda nicknamed her husband “The Rock” because he would “just stand firm on everything and anything.”

Stanback had plenty of time to devote to representing his constituents, as Greyhound bus drivers had been on a long strike throughout the early 1990s, severely limiting his driving duties.

During his time in office, he played a key role procuring new playground equipment for the South Albemarle Park.

He admits he had some rough experiences with some of his fellow members, although he had a long-lasting friendship with the late Roy Talbert. Frequently, Talbert seconded motions offered up by Stanback, he said.

As someone never afraid to voice his opinion, even if it went against most of the other members, Stanback was adamantly opposed to the Public Housing Authority, which was its own entity, coming under the jurisdiction of the city in the early 1990s.

All these many years later, Stanback said he believes public housing would be better off operating independently of the city.

When looking back on his career, Stanback said he is uncomfortable with claiming credit for much of the change he helped bring about, emphasizing that it was a team effort.

“I just don’t want to say I’m responsible for anything,” he said. “I just do the best I can do.”